“Complexity is your enemy. Any fool can make something complicated. It’s hard to keep things simple.”

-Richard Branson.

Private equity has long been viewed as an exclusive asset class, often associated with institutional investors and ultra-high-net-worth portfolios. In recent years, however, access to private equity has expanded, prompting many investors to ask whether it deserves a place alongside traditional stocks and bonds. While private equity can offer compelling return potential and diversification benefits, it also introduces unique risks, liquidity constraints, and structural complexities that are not always well understood. This paper explores what private equity is, how it works within a portfolio, and the key considerations investors should weigh when deciding whether private equity aligns with their long-term goals.

Private Equity – sounds cool, but what is it?

Private equity refers to investments made in companies that are not publicly traded on a stock exchange. Rather than buying shares in the open market, private equity investors provide capital directly to businesses – often to support growth initiatives, operational improvements, or ownership transitions. These investments are typically held for several years, with returns generated through business expansion, improved profitability, and eventual sale or public offering. Because private equity investments are illiquid and may require active management, they differ meaningfully from traditional public stock investments in both structure and risk profile.

Private equity has historically been an institutional asset class, popularized by large endowments such as Yale under the leadership of David Swensen, often regarded as the architect of the modern endowment model. The success of this approach, however, relied on structural advantages unique to large institutions – advantages that are not easily replicated by individual investors. These institutions are perpetual in nature, have highly predictable capital inflows, and can commit capital for extended periods without concern for short-term liquidity or interim performance.

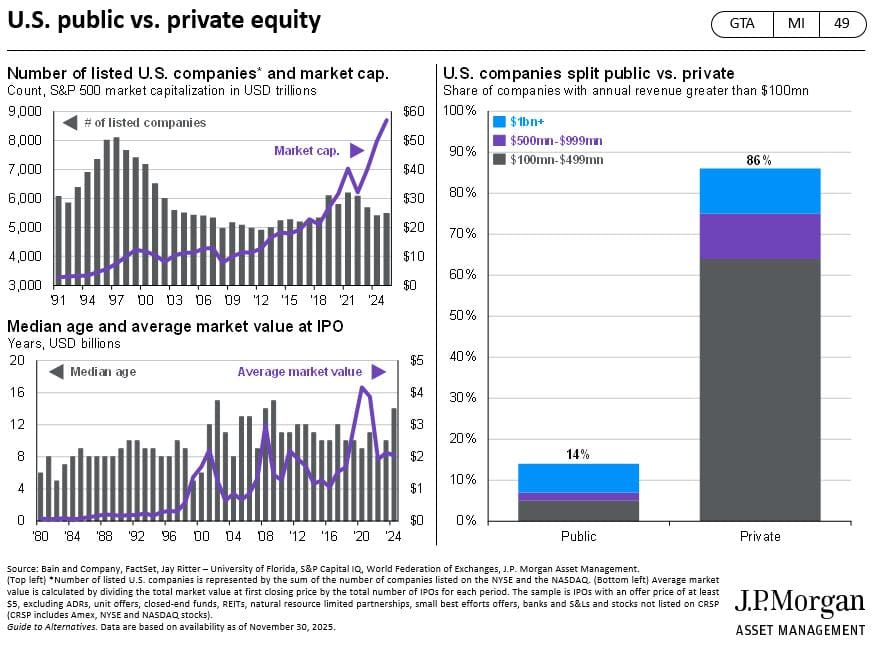

You may have heard of SpaceX, OpenAI (Creator of ChatGPT), or Epic Games (video game publisher) as exciting companies that are growing, yet you cannot purchase shares of these companies on traditional stock exchanges. That is because many of today’s most influential and recognizable companies – spanning technology, consumer brands, and industrial leaders – remain privately owned, meaning investors generally cannot access them through public stock markets and instead must rely on private equity or private market vehicles for exposure.

The flip side of this is that for every big winner or recognizable private business that has a successful exit, there are dozens that failed or underperformed. The nature of the game is to have enough big winners that have 20-, 50-, or 100-fold returns to balance out the volume of bets that inevitably do very poorly or even go to zero.

Private equity is becoming increasingly more prominent as companies are choosing to remain private for longer because the benefits of accessing public markets increasingly come with meaningful trade-offs. Staying private allows management teams to focus on long-term strategic decisions without the pressure of quarterly earnings expectations, public market volatility, or activist scrutiny. Private ownership can also offer greater flexibility around capital structure, operational changes, and investment timelines, while avoiding the regulatory, reporting, and compliance costs associated with being a public company. As private capital has become more abundant, companies are often able to raise significant funding and pursue growth objectives without the need to go public, reducing the urgency of an IPO.

In summary, private equity represents a distinct approach to investing that emphasizes long-term ownership, active involvement, and value creation outside the public markets. While the underlying goal – growing the value of a business – is similar to public equity investing, the structure, time horizon, and risks are meaningfully different. Understanding these differences is essential before considering private equity as part of a broader portfolio. In the sections that follow, we outline the key characteristics of private equity investments and explain how they can influence returns, risk, and overall portfolio construction.

Key Investment Characteristics and Concerns

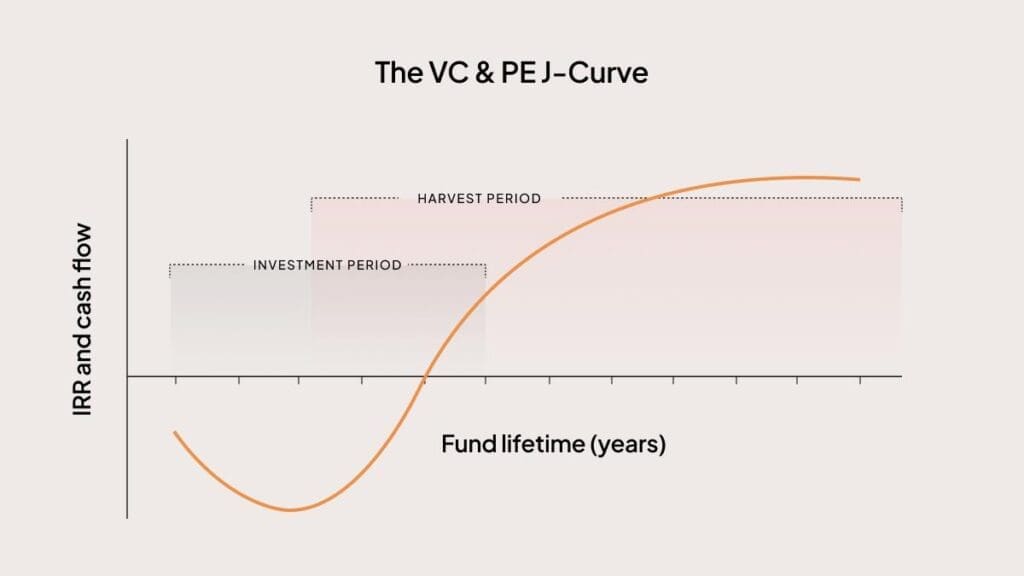

Typically, institutions and high-net-worth individuals access private equity markets by committing capital to a fund manager to invest. Most private equity funds are structured with an expected life of approximately 10 years, during which investor capital is drawn down gradually in the early years as investments are made and later returned as portfolio companies are sold or taken public.

In the early years of a private equity fund, returns often appear negative because capital is being invested and costs are incurred before meaningful value is realized, with performance improving over time as portfolio companies mature and are eventually sold.

Because of their long-term structure and gradual capital deployment, private equity investments are not designed to generate quick gains or short-term liquidity. Capital is typically committed for many years, with limited ability to access or exit the investment prior to the fund’s maturity.

This illiquidity is one of the most important considerations for investors, as capital may be tied up through market cycles and periods of volatility. While illiquidity can be compensated by higher return potential over time, it requires careful planning and a long-term mindset to ensure that private equity aligns with an investor’s overall financial goals and liquidity needs.

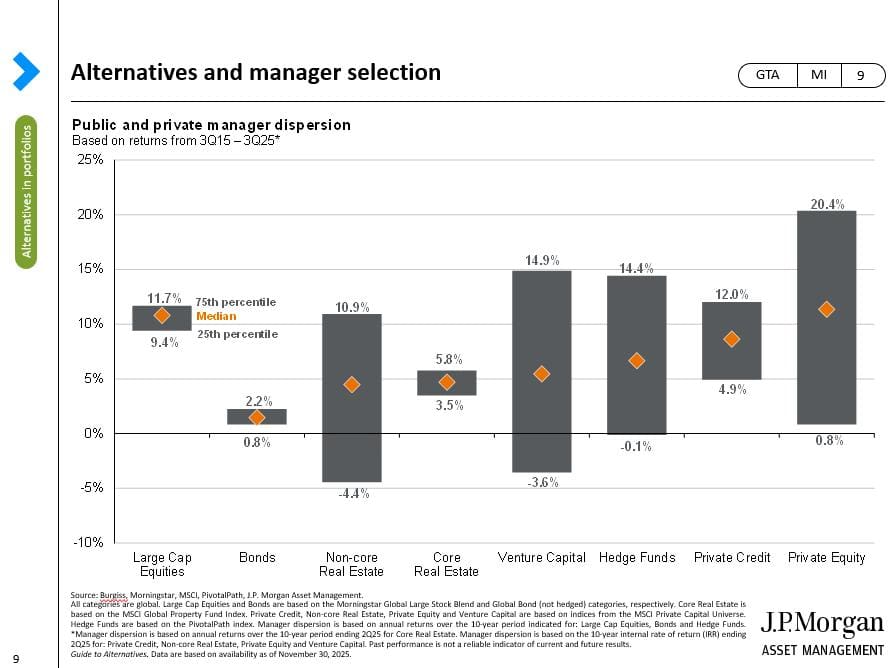

Beyond structure and liquidity, one of the most important determinants of private equity outcomes is manager selection. Unlike public markets, where returns are often driven by broad market movements, private equity results can vary widely from one manager to another based on experience, discipline, sourcing capabilities, and execution. The dispersion of returns across private equity managers is significant, making due diligence and partner selection a critical component of successfully incorporating private equity into a portfolio.

As illustrated in the chart above, the difference in outcomes between top- and bottom-quartile managers is relatively modest in traditional public markets. In large-cap equities, the return spread between the best and worst managers is approximately 4.3%, while in public fixed income the spread narrows further to roughly 1.4%. This narrower dispersion reflects the efficiency and transparency of public markets, where manager skill, while important, tends to have a more limited impact on long-term results.

In contrast, return dispersion is significantly wider in private markets. In private equity and venture capital, the spread between top- and bottom-quartile managers expands dramatically to approximately 19.6% and 18.5%, respectively. This highlights both the opportunity and the risk inherent in these asset classes. While private equity can offer meaningful return enhancement and diversification when paired with top-tier managers – evidenced by top-quartile private equity returns of 20.4% compared to 11.7% for top-quartile large-cap equities – those benefits diminish quickly when manager selection falters. Median private equity managers have delivered returns similar to public equities, and bottom-quartile private equity managers have produced near-flat returns over the past decade, materially underperforming even the weakest public equity managers.

History tells us if you cannot access a top-quartile manager (something that isn’t known in advance), the expected outcome of private equity investing is roughly equivalent to buying a low-cost S&P 500 index fund, but with the 10-year illiquidity and substantially higher fees, the median private equity investor is not being compensated for the illiquidity they’re accepting.

These dynamics underscore why manager selection is a critical component of private equity investing, where outcomes are far less driven by market exposure and far more dependent on execution, discipline, and access to high-quality opportunities.

Critically, elite private equity managers have historically been highly selective about their investor base. Access to top-tier funds has often been reserved for large, influential institutions capable of committing significant capital, negotiating favorable terms, and accepting long lock-up periods. In many cases, even sophisticated individual investors or large wealth platforms have been unable to gain access to these managers. As a result, institutions like Yale have benefited from lower fees, more flexible liquidity terms, and preferential fund structures that are generally unavailable to individual investors.

Another important consideration in private equity is the fee structure. Private equity funds typically charge both a management fee (often in the range of 1–2%) and an incentive fee, commonly referred to as carried interest. Carried interest represents a profit-sharing arrangement that applies once returns exceed a predetermined threshold, known as the hurdle rate. A common private equity fee structure is described as “2 and 20,” meaning a 2% annual management fee and a 20% incentive fee on profits earned above the hurdle rate. Understanding the fee structure of each private equity fund is extremely important and can be a bit technical, so caution is advised.

So, to summarize some of the challenges of private equity: investors must contend with illiquidity in the form of long, often ten-year fund lockups; returns that tend to diminish outside of top-quartile managers who are themselves capacity-constrained; and materially higher management fees. And if things go well, the manager participates meaningfully in the upside through incentive fees.

So should investors just avoid the asset class altogether?

Not necessarily. For the right type of investor, private equity can still play a valuable role when used thoughtfully and in moderation. The key is recognizing that private equity is not a replacement for public markets, nor is it appropriate for every portfolio. Instead, it is best viewed as a complementary allocation for qualified investors who have long time horizons, ample liquidity elsewhere in their portfolio, and a clear understanding of the trade-offs involved.

We see private equity implemented with success for clients who take a multi-generational approach, or investors with long investment horizons who are seeking to maximize their long-term, risk-adjusted return profile. This often includes families whose primary objective is not near-term income or liquidity, but rather long-term capital growth to support future generations, philanthropic goals, or both.

For these investors, private equity can serve as a tool for long-term value creation, helping to grow capital in a way that supports wealth-building objectives. Because these clients are typically less reliant on portfolio liquidity and more focused on maximizing total wealth over decades rather than years, they are often better positioned to tolerate the illiquidity and return variability inherent in private equity investing.

Private equity may also be well-suited for younger, high-earning professionals or entrepreneurs who have experienced significant liquidity events and have both the financial capacity and emotional discipline to commit capital for extended periods. With long time horizons ahead of them, these investors can allow private equity strategies to fully mature across market cycles, benefiting from compounding and long-term operational value creation rather than short-term market movements.

In each of these cases, the common thread is flexibility – flexibility around time horizon, cash flow needs, and liquidity. Clients who can afford to view private equity as a long-term allocation rather than a tactical investment are often best positioned to capture its potential benefits, particularly when the allocation is sized appropriately and integrated thoughtfully within a broader, diversified portfolio.

When implemented properly, private equity can provide access to parts of the economy that are increasingly difficult to reach through public markets alone. Many high-quality businesses now remain private for longer periods, meaning a significant portion of value creation occurs before any potential public listing. Private equity offers investors a way to participate in this growth, particularly within the middle market, where active ownership and operational improvements can drive long-term value.

Moreover, using a fund-of-funds structure can help address several of the historical challenges associated with private equity investing. By diversifying across managers, strategies, geographies, and vintage years, these vehicles reduce reliance on any single outcome and help smooth return variability. For private wealth investors who lack institutional scale or direct access to elite managers, this approach can provide a more disciplined and diversified entry point into the asset class.

However, it should be stated that fund-of-funds typically have higher fees than typical direct private equity funds. Our opinion is that a fund-of-funds approach can be value-additive if the manager has access to capacity-constrained fund managers and provides diversification across different market segments, such as venture capital and buyout private equity.

In this context, private equity should not be viewed as a default allocation, but rather as a specialized tool – one that, when appropriately sized and paired with strong manager selection, can enhance long-term portfolio outcomes for certain qualified investors.

This material is for informational purposes only and is not intended as personalized investment advice. Advisory services are provided through FourThought Financial Partners, LLC, a registered investment adviser with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). SEC registration does not imply a certain level of skill and/or expertise.

The information provided is not meant to be a solicitation or recommendation to buy/sell any specific securities. Please consult your Financial Advisor to discuss the risks associated with these types of investments. Private equity investments are generally not publicly traded and lack a secondary market, making them difficult to value or liquidate, potentially resulting in the inability to sell at fair value or at all. Private investments in general are limited for purchase only to those who are accredited and sophisticated investors. Past performance is not indicative of future results.